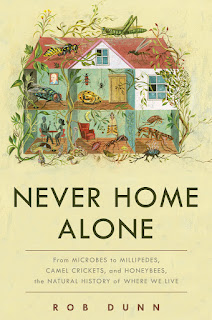

The New York Times review of Rob Dunn's new book Never Home Alone: From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets, and Honey Bees, the Natrual History of Where We Live (2018, New York: Basic Books, 307 pp.), calls it "a book that will make you terrified of your own house." To the contrary, it is a celebration of the biodiversity of the indoors. Presented here are solid scientific arguments for re-thinking how we approach our daily lives.

Dunn is among the most prolific science writer of our time, but the rigor and research he applies to each book is beyond reproach. He is also captivating in his delivery, a master at never talking down to the reader, but instead elevating the reader into a participant role in the storytelling. Indeed, my reaction to some passages was "why didn't I get invited to help with that study?" or "how do I get to help in the next research project?" Dunn's enthusiasm and sense of wonder are far more contagious than any of the pathogenic microbes he discusses in Never Home Alone.

About those bacteria, yeasts, molds, fungi, and viruses. Turns out that there is untold diversity among them, and the overwhelming majority are beneficial to us rather than malignant. In the course of surveying homes around the world, from his own neighborhood in Raleigh, North Carolina to Russia, and even the international space station, Dunn and his minions discovered new species of microbes. Probably new genera and families, too. How is it that we still have so much to learn about the places we spend ninety percent of our lives? He has a theory, but you will find no spoilers here.

Dunn puts the "history" in "natural history" in all of his books, and it is often a history we do not learn of in school, certainly not to the depths that various historical figures and episodes deserve. Here, that history demonstrates where science has been confronted with choices, and how civilization has progressed, or potentially strayed, as a result of the paths we have taken.

The overall message of Never Home Alone is a positive and encouraging one. It is always the disasters and exceptions that make the headlines. How black mold turns homes into lethal chambers for the human residents. The latest epidemic of Staphylococcus bacteria in the local hospital. Not publicized are the numerous microbes, insects, fungi, and other organisms found in the average home or workplace that are essential to our human lives. We are overzealous in our efforts to rid our homes of harmful creatures, eradicating the helpful and inert species with far greater success, albeit inadvertently. The dangerous critters prosper through evolved resistance to chemical treatment, and the absence of the good creatures that would outcompete them if we did little or nothing to intervene.

Dunn stops short of stating the ultimately obvious: "Product" and "service" are rarely the answer to any problem, especially an ailing household. Something is already out of balance, and applying chemical treatments is only going to exacerbate the situation rather than solve it. Your home, workplace, and even your body are ecosystems, mostly at a microscopic scale, and failure to treat them as such, to cultivate the beneficial species, is asking for trouble.

Never Home Alone concludes with a chapter about bread, specifically sourdough, which results from fermentation processes conducted by yeasts in concert with other microbes. Bread is a living thing, or more properly a collection of living things, like an orchestra, bread being the musical product. It is an apt metaphor for how we should approach every aspect of our lives. We should be striving to be a complement to other species, fostering diversity at every level. When we seek to understand, ask questions first, and hesitate before reaching for the cleansing fluid, we begin to truly flourish. Our potential as stewards of the planet begins, literally, at home. Stop with the apologies, the "excuse the mess" greeting you give your guests. You are not a messy housekeeper, you are promoting biodiversity. Read this book and free yourself.